Electrical generator

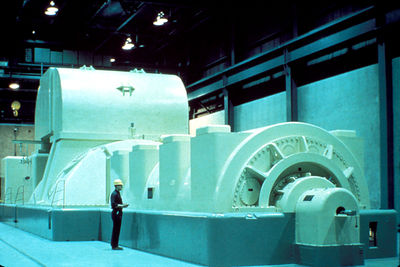

In electricity generation, an electric generator is a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy. The reverse conversion of electrical energy into mechanical energy is done by a motor; motors and generators have many similarities. A generator forces electrons in the windings to flow through the external electrical circuit. It is somewhat analogous to a water pump, which creates a flow of water but does not create the water inside. The source of mechanical energy may be a reciprocating or turbine steam engine, water falling through a turbine or waterwheel, an internal combustion engine, a wind turbine, a hand crank, compressed air or any other source of mechanical energy.

Contents |

Historical developments

Before the connection between magnetism and electricity was discovered, electrostatic generators were invented that used electrostatic principles. These generated very high voltages and low currents. They operated by using moving electrically charged belts, plates and disks to carry charge to a high potential electrode. The charge was generated using either of two mechanisms:

- Electrostatic induction

- The triboelectric effect, where the contact between two insulators leaves them charged.

Because of their inefficiency and the difficulty of insulating machines producing very high voltages, electrostatic generators had low power ratings and were never used for generation of commercially-significant quantities of electric power. The Wimshurst machine and Van de Graaff generator are examples of these machines that have survived.

Jedlik's dynamo

In 1827, Hungarian Anyos Jedlik started experimenting with electromagnetic rotating devices which he called electromagnetic self-rotors. In the prototype of the single-pole electric starter (finished between 1852 and 1854) both the stationary and the revolving parts were electromagnetic. He formulated the concept of the dynamo at least 6 years before Siemens and Wheatstone but didn't patent it as he thought he wasn't the first to realize this. In essence the concept is that instead of permanent magnets, two electromagnets opposite to each other induce the magnetic field around the rotor. It was also the discovery of the principle of self-excitation.[1] Jedlik's invention was decades ahead of its time.

Faraday's disk

In the years of 1831-1832 Michael Faraday discovered the operating principle of electromagnetic generators. The principle, later called Faraday's law, is that a potential difference is generated between the ends of an electrical conductor that moves perpendicular to a magnetic field. He also built the first electromagnetic generator, called the 'Faraday disk', a type of homopolar generator, using a copper disc rotating between the poles of a horseshoe magnet. It produced a small DC voltage.

This design was inefficient due to self-cancelling counterflows of current in regions not under the influence of the magnetic field. While current flow was induced directly underneath the magnet, the current would circulate backwards in regions outside the influence of the magnetic field. This counterflow limits the power output to the pickup wires, and induces waste heating of the copper disc. Later homopolar generators would solve this problem by using an array of magnets arranged around the disc perimeter to maintain a steady field effect in one current-flow direction.

Another disadvantage was that the output voltage was very low, due to the single current path through the magnetic flux. Experimenters found that using multiple turns of wire in a coil could produce higher more useful voltages. Since the output voltage is proportional to the number of turns, generators could be easily designed to produce any desired voltage by varying the number of turns. Wire windings became a basic feature of all subsequent generator designs.

However, recent advances (rare earth magnets) have made possible homo-polar motors with the magnets on the rotor, which should offer many advantages to older designs.

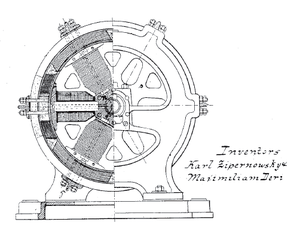

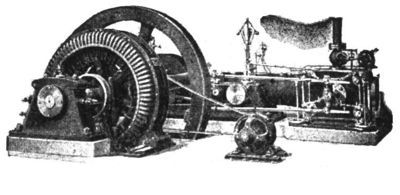

Dynamo

The Dynamo was the first electrical generator capable of delivering power for industry. The dynamo uses electromagnetic principles to convert mechanical rotation into a pulsing direct electric current through the use of a commutator. The first dynamo was built by Hippolyte Pixii in 1832.

Through a series of accidental discoveries, the dynamo became the source of many later inventions, including the DC electric motor, the AC alternator, the AC synchronous motor, and the rotary converter.

A dynamo machine consists of a stationary structure, which provides a constant magnetic field, and a set of rotating windings which turn within that field. On small machines the constant magnetic field may be provided by one or more permanent magnets; larger machines have the constant magnetic field provided by one or more electromagnets, which are usually called field coils.

Large power generation dynamos are now rarely seen due to the now nearly universal use of alternating current for power distribution and solid state electronic AC to DC power conversion. But before the principles of AC were discovered, very large direct-current dynamos were the only means of power generation and distribution. Now power generation dynamos are mostly a curiosity.

Other rotating electromagnetic generators

Without a commutator, the dynamo is an example of an alternator, which is a synchronous singly-fed generator. With an electromechanical commutator, the dynamo is a classical direct current (DC) generator. The alternator must always operate at a constant speed that is precisely synchronized to the electrical frequency of the power grid for non-destructive operation. The DC generator can operate at any speed within mechanical limits but always outputs a direct current waveform.

Other types of generators, such as the asynchronous or induction singly-fed generator, the doubly-fed generator, or the brushless wound-rotor doubly-fed generator, do not incorporate permanent magnets or field windings (i.e, electromagnets) that establish a constant magnetic field, and as a result, are seeing success in variable speed constant frequency applications, such as wind turbines or other renewable energy technologies.

The full output performance of any generator can be optimized with electronic control but only the doubly-fed generators or the brushless wound-rotor doubly-fed generator incorporate electronic control with power ratings that are substantially less than the power output of the generator under control, which by itself offer cost, reliability and efficiency benefits.

MHD generator

A magnetohydrodynamic generator directly extracts electric power from moving hot gases through a magnetic field, without the use of rotating electromagnetic machinery. MHD generators were originally developed because the output of a plasma MHD generator is a flame, well able to heat the boilers of a steam power plant. The first practical design was the AVCO Mk. 25, developed in 1965. The U.S. government funded substantial development, culminating in a 25 MW demonstration plant in 1987. In the Soviet Union from 1972 until the late 1980s, the MHD plant U 25 was in regular commercial operation on the Moscow power system with a rating of 25 MW, the largest MHD plant rating in the world at that time.[2] MHD generators operated as a topping cycle are currently (2007) less efficient than combined-cycle gas turbines.

Terminology

The two main parts of a generator or motor can be described in either mechanical or electrical terms:[3]

Mechanical:

- Rotor: The rotating part of an electrical machine

- Stator: The stationary part of an electrical machine

Electrical:

- Armature: The power-producing component of an electrical machine. In a generator, alternator, or dynamo the armature windings generate the electrical current. The armature can be on either the rotor or the stator.

- Field: The magnetic field component of an electrical machine. The magnetic field of the dynamo or alternator can be provided by either electromagnets or permanent magnets mounted on either the rotor or the stator.

Because power transferred into the field circuit is much less than in the armature circuit, AC generators nearly always have the field winding on the rotor and the stator as the armature winding. Only a small amount of field current must be transferred to the moving rotor, using slip rings. Direct current machines necessarily have the commutator on the rotating shaft, so the armature winding is on the rotor of the machine.

Excitation

An electric generator or electric motor that uses field coils rather than permanent magnets will require a current flow to be present in the field coils for the device to be able to work. If the field coils are not powered, the rotor in a generator can spin without producing any usable electrical energy, while the rotor of a motor may not spin at all. Very large power station generators often utilize a separate smaller generator to excite the field coils of the larger.

In the event of a severe widespread power outage where islanding of power stations has occurred, the stations may need to perform a black start to excite the fields of their largest generators, in order to restore customer power service.

DC Equivalent circuit

G = generator

VG=generator open-circuit voltage

RG=generator internal resistance

VL=generator on-load voltage

RL=load resistance

The equivalent circuit of a generator and load is shown in the diagram to the right. The generator's  and

and  parameters can be determined by measuring the winding resistance (corrected to operating temperature), and measuring the open-circuit and loaded voltage for a defined current load.

parameters can be determined by measuring the winding resistance (corrected to operating temperature), and measuring the open-circuit and loaded voltage for a defined current load.

Vehicle-mounted generators

Early motor vehicles until about the 1960s tended to use DC generators with electromechanical regulators. These have now been replaced by alternators with built-in rectifier circuits, which are less costly and lighter for equivalent output. Automotive alternators power the electrical systems on the vehicle and recharge the battery after starting. Rated output will typically be in the range 50-100 A at 12 V, depending on the designed electrical load within the vehicle. Some cars now have electrically-powered steering assistance and air conditioning, which places a high load on the electrical system. Large commercial vehicles are more likely to use 24 V to give sufficient power at the starter motor to turn over a large diesel engine. Vehicle alternators do not use permanent magnets and are typically only 50-60% efficient over a wide speed range.[4] Motorcycle alternators often use permanent magnet stators made with rare earth magnets, since they can be made smaller and lighter than other types. See also hybrid vehicle.

Some of the smallest generators commonly found power bicycle lights. These tend to be 0.5 ampere, permanent-magnet alternators supplying 3-6 W at 6 V or 12 V. Being powered by the rider, efficiency is at a premium, so these may incorporate rare-earth magnets and are designed and manufactured with great precision. Nevertheless, the maximum efficiency is only around 80% for the best of these generators—60% is more typical—due in part to the rolling friction at the tire-generator interface from poor alignment, the small size of the generator, bearing losses and cheap design. The use of permanent magnets means that efficiency falls even further at high speeds because the magnetic field strength cannot be controlled in any way. Hub generators remedy many of these flaws: internal to the bicycle hub, they are well manufactured and don't require an interface between the generator and tire. Until recently, these generators have been expensive and hard to find. Major bicycle component manufacturers like Shimano and SRAM have only just entered this market. However, expect significant gains in future as bicycling becomes more mainstream transportation and LED technology allows brighter lighting at the reduced current these generators are capable of providing.

Sailing yachts may use a water or wind powered generator to trickle-charge the batteries. A small propeller, wind turbine or impeller is connected to a low-power alternator and rectifier to supply currents of up to 12 A at typical cruising speeds.

Engine-generator

An engine-generator is the combination of an electrical generator and an engine (prime mover) mounted together to form a single piece of self-contained equipment. The engines used are usually piston engines, but gas turbines can also be used. Many different versions are available - ranging from very small portable petrol powered sets to large turbine installations.

Human powered electrical generators

A generator can also be driven by human muscle power (for instance, in field radio station equipment).

Human powered direct current generators are commercially available, and have been the project of some DIY enthusiasts. Typically operated by means of pedal power, a converted bicycle trainer, or a foot pump, such generators can be practically used to charge batteries, and in some cases are designed with an integral inverter. The average adult could generate about 125-200 watts on a pedal powered generator. Portable radio receivers with a crank are made to reduce battery purchase requirements, see clockwork radio.

Linear electric generator

In the simplest form of linear electric generator, a sliding magnet moves back and forth through a solenoid - a spool of copper wire. An alternating current is induced in the loops of wire by Faraday's law of induction each time the magnet slides through. This type of generator is used in the Faraday flashlight. Larger linear electricity generators are used in wave power schemes.

Tachogenerator

Tachogenerators are frequently used to power tachometers to measure the speeds of electric motors, engines, and the equipment they power. Generators generate voltage roughly proportional to shaft speed. With precise construction and design, generators can be built to produce very precise voltages for certain ranges of shaft speeds

See also

- Faraday's law of induction

- Alternator

- Homopolar generator

- Superconducting electric machine

- Hybrid vehicle

- Solar cell

- Radioisotope thermoelectric generator

- Thermogenerator

- Wind turbine

- Diesel generator

References

- ↑ Augustus Heller (April 2, 1896), "Anianus Jedlik", Nature (Norman Lockyer) 53 (1379): 516, http://books.google.com/books?id=nWojdmTmch0C&pg=PA516&dq=jedlik+dynamo+1827&lr=&as_brr=3&ei=12p_SvDFGZv8lASZxbDOAQ#v=onepage&q=jedlik%20dynamo%201827&f=false

- ↑ Langdon Crane, Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) Power Generator: More Energy from Less Fuel, Issue Brief Number IB74057, Library of Congress Congressional Research Service, 1981, retrieved from http://digital.library.unt.edu/govdocs/crs/permalink/meta-crs-8402:1 July 18, 2008

- ↑ James Stallcup (2005). Stallcup's Generator, Transformer, Motor And Compressor Book, 2005. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 2-1. ISBN 9780877656692. http://books.google.com/books?id=OkwGeMAXJa8C&pg=PT22&dq=generator+terms+armature+rotor+stator+field+mechanical+electrical&num=20&ei=2jTlStQBiMyVBKSpgJEM#v=onepage&q=generator%20terms%20armature%20rotor%20stator%20field%20mechanical%20electrical&f=false.

- ↑ Horst Bauer Bosch Automotive Handbook 4th Edition Robert Bosch GmbH, Stuttgart 1996 ISBN 0-8376-0333-1, page 813

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||